维特根斯坦——逻辑哲学论

素学研究

本书是路德维希·维特根斯坦生前唯一的出版物,罗素认为,它要解决的核心问题是:

语言与世界之间必须存在什么样的关系,才能使任何一个语词(无论它是什么)能够成为一个事实的符号?

罗素将《逻辑哲学论》视为一种形而上学理论,即它揭示了世界必须具有的某种逻辑结构。而维特根斯坦则认为,他是在澄清语言的逻辑语法,而不是在提出关于世界本体的理论。他展示的是“我们如何看世界”,而不是“世界本身是什么”。

维特根斯坦的大致思路是,澄清如何在语言中使用逻辑,阐释世界、语言、逻辑、思想和事态的关系,从中找到我们身处世界容器之中可以持有的某种世界观,讨论哪些可以说(自然科学、事实),哪些可以不言而明(逻辑形式),哪些不可言说(伦理、美学、生命的意义),并对不可言说之事要保持沉默,最后:

我的命题应当是以如下方式来起阐明作用的:任何理解我的人,当他应用这些命题作为梯子而爬过了它们之后,终于会认识到它们是没有任何意义的。(可以说,在登上高处之后,他必须把梯子扔掉。)

之所以用英译版本,是为了最大程度消解翻译本身增加的障碍(虽然不是德语)。

TRACTATUS LOGICO-PHILOSOPHICUS

Dedicated to the memory of my friend David H. Pinsent

Motto: …and everything one knows, not merely heard as rumbling and roaring, can be said in three words. — Kürnberger*

PREFACE

This book will perhaps be understood only by someone who has already thought the thoughts expressed in it themselves—or at any rate similar thoughts. It is thus not a textbook. Its purpose would be achieved if it gave pleasure to one person who read it with understanding.

The book treats the problems of philosophy and shows—I believe—that the posing of these problems rests on misunderstanding the logic of our language. The whole sense of the book might be captured in these words: what can be said at all can be said clearly; and of what one cannot talk, about that one must be silent.\*

The book thus aims to draw a limit to thinking, or rather, not to thinking but to the expression of thoughts: for to draw a limit to thinking, we would have to be able to think both sides of this limit (that is, we would have to be able to think what cannot be thought).

The limit will thus only be drawable in language and what lies on the other side of the limit will simply be nonsense.

How far my efforts coincide with those of other philosophers I have no wish to judge. What I have written here makes no claim at all to novelty in detail; and the reason I give no references is that I am not concerned with whether what I have thought has already been thought by someone else before me.

I only want to mention that I am indebted to the magnificent works of Frege and the writings of my friend Mr Bertrand Russell for a large part of the stimulation of my thoughts.

If this work has a value, then it consists in two things. First, in that thoughts are expressed in it, and this value will be greater the better the thoughts are expressed, the more the nail has been hit on the head.—Here I am conscious that I have fallen far short of what is possible, simply because my powers are too weak to accomplish the task.—May others come and do it better.

On the other hand it seems to me that the truth of the thoughts conveyed here is unassailable and definitive. I am thus of the view that the problems in essence have been finally solved. And if I am not mistaken in this, then the value of this work consists, secondly, in showing how little is done when these problems are solved.

L.W.

Vienna, 1918

1 The world is everything that is the case

1.1 The world is the totality of facts, not of things.

1.11 The world is determined by the facts and by their being all the facts.

1.12 For the totality of facts determines what is the case as well as everything that is not the case.

1.13 The facts in logical space are the world.

1.2 The world divides into facts.

1.21 Something can be the case or not the case and everything else remain the same.

2 What is the case, a fact, is the obtaining of states-of-things

2.01 A state-of-things is a combination of objects (entities, things).\*

2.011 It is essential to a thing that it can be a constituent of a state-of-things.

2.012 In logic nothing is accidental: if a thing can occur in a state-of-things, then the possibility of the state-of-things must already be prefigured\* in the thing.

2.0121 It would appear as an accident, as it were, if a state of affairs were subsequently to fit a thing that could exist in and by itself.

If things can occur in states-of-things, then this possibility must already lie in them.

(What is logical cannot be merely possible. Logic deals with every possibility and all possibilities are its facts.)

Just as we cannot think of spatial objects at all outside space, or temporal objects outside time, so we cannot think of any object outside the possibility of its combination with other objects.

If I can think of an object in the context of a state-ofthings, then I cannot think of it outside the possibility of this context.

2.0122 A thing is independent insofar as it can occur in all possible states of affairs, but this form of independence is a form of connection with a state-of-things, a form of dependence. (It is impossible for words to appear in two different ways, on their own and in a proposition.\*)

2.0123 If I know\* an object, then I also know all the possibilities of its occurrence in states-of-things.

(Every such possibility must lie in the nature of the object.)

A new possibility cannot be found subsequently.

2.01231 To know an object, I do not need to know its external properties—but I must know all its internal properties.

2.0124 If all objects are given, then all possible states-of-things are thereby also given.

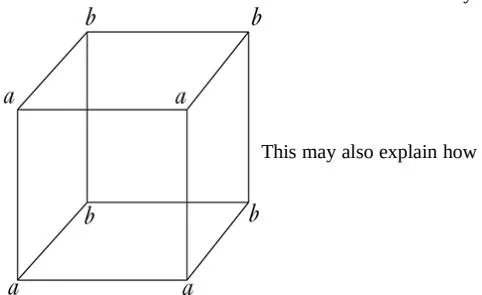

2.013 Every thing is, as it were, in a space of possible states-ofthings. I can think of this space as empty, but not of the thing without the space.

2.0131 A spatial object must lie in infinite space. (A spatial point is an argument-place.)

A spot in the visual field need not be red, but it must have some colour: it has, so to speak, a colour space around it. A sound must have some pitch, an object of touch some hardness, and so on.

2.014 Objects contain the possibility of all states of affairs.\*

2.0141 The possibility of its occurrence in states-of-things is the form of an object.

2.02 An object is simple.\*

2.0201 Every statement about complexes can be analysed into a statement about their constituents and into those propositions that describe the complexes completely.

2.021 Objects form the substance of the world. That is why they cannot be composite.

2.0211 If the world had no substance, then whether a proposition

had sense would depend on whether another proposition was true.

2.0212 It would then be impossible to draw up a picture of the world (true or false).

2.022 It is obvious that an imagined world, however different from the real world it may be, must have something—a form—in common with the real world.

2.023 This fixed form consists simply of the objects.

2.0231 The substance of the world can only determine a form and not any material properties. For these are only represented\* by propositions—only formed by the configuration of objects.

2.0232 Roughly speaking: objects are colourless.

2.0233 Two objects of the same logical form—aside from their external properties—are only distinguished from one another in that they are different.

2.02331 Either a thing has properties that nothing else has, in which case one can single it out from others straightaway by a description and refer to it;\* or, instead, there are several things that have all their properties in common, in which case it is quite impossible to point to one of them.

For if a thing is not distinguished by anything, then I cannot distinguish it, for otherwise it would be distinguished.

2.024 Substance is what subsists\* independently of what is the case.

2.025 It is form and content.

2.0251 Space, time and colour (colouration) are forms of objects.

2.026 Only if there are objects can there be a fixed form of the world.

2.027 The fixed, the subsistent\* and the object are one.

2.0271 The object is the fixed, the subsistent; the configuration is the changing, the inconstant.\*

2.0272 The configuration of objects forms the state-of-things.

2.03 In a state-of-things the objects hang in one another, like the links of a chain.

2.031 In a state-of-things the objects stand to one another in a determinate way.\*

2.032 The way in which the objects connect\* in a state-of-things is the structure of the state-of-things.

2.033 The form is the possibility of the structure.

2.034 The structure of the fact consists of the structures of the states-of-things.

2.04 The totality of the obtaining states-of-things is the world.

2.05 The totality of the obtaining states-of-things also determines which states-of-things do not obtain.

2.06 The obtaining and non-obtaining of states-of-things is reality. (The obtaining of states-of-things we also call a positive, the non-obtaining a negative fact.)

2.061 States-of-things are independent of one another.

2.062 From the obtaining or non-obtaining of a state-of-things, the obtaining or non-obtaining of another cannot be inferred.

2.063 The totality of reality is the world.

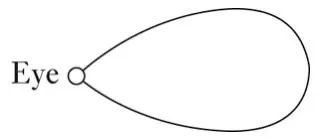

2.1 We picture facts.\*

2.11 A picture presents\* a state of affairs in logical space, the obtaining and non-obtaining of states-of-things.

2.12 A picture is a model of reality.

2.13 In a picture, the elements of the picture correspond to the objects.

2.131 In a picture, the elements of the picture stand for the objects.

2.14 A picture consists in its elements standing to one another\*

in a determinate way.

2.141 A picture is a fact.

2.15 That the elements of a picture stand to one another in a determinate way presents\* that things stand to one another in this way.

This connection of the elements of a picture may be called its structure, and the possibility of this structure its form of depiction.

2.151 The form of depiction is the possibility that things stand to one another in the same way as the elements of the picture do.

2.1511 It is in this way that a picture is connected\* to reality; it reaches up to it.

2.1512 It is laid against reality like a measure.

2.15121 Only the outermost points of the dividing lines touch the object to be measured.

2.1513 On this conception, the depicting relation that makes it a picture thus also belongs to the picture.

2.1514 The depicting relation consists of the correlations of the elements of the picture and the things.\*

2.1515 These correlations are, as it were, the feelers\* of the picture’s elements with which the picture touches reality.

2.16 To be a picture, a fact must have something in common with what is depicted.

2.161 There must be something identical in picture and depicted if the one is to be capable of being a picture of the other at all.

2.17 What a picture must have in common with reality to be able to depict it in the way it does—correctly or incorrectly —is its form of depiction.

2.171 A picture can depict any reality whose form it has. A spatial picture anything spatial, a coloured anything coloured, etc.

| 2.172 | A picture cannot depict, however, its form of depiction; it features it.* | |

|---|---|---|

| 2.173 | A picture represents its object from outside (its standpoint is its form of representation); this is why a picture represents its object correctly or incorrectly. | |

| 2.174 | A picture cannot, however, place itself outside its form of representation. | |

| 2.18 | What any picture, of whatever form, must have in common with reality to be able to depict it at all—correctly or incorrectly—is logical form, that is, the form of reality. | |

| 2.181 | If the form of depiction is logical form, then the picture is a logical picture. | |

| 2.182 | Every picture is also a logical picture. (On the other hand, not every picture is a spatial picture, for example.) | |

| 2.19 | A logical picture can depict the world. | |

| 2.2 | A picture has the logical form of depiction in common with what is depicted. | |

| 2.201 | A picture depicts reality by representing a possibility of the obtaining and non-obtaining of states-of things.* | |

| 2.202 | A picture represents a possible state of affairs in logical space. | |

| 2.203 | A picture contains the possibility of the state of affairs that it represents. | |

| 2.21 | A picture agrees with reality or not; it is correct or incorrect, true or false. | |

| 2.22 | A picture represents what it represents, independently of its truth or falsity, through its form of depiction. | |

| 2.221 | What a picture represents is its sense. | |

| 2.222 | Its truth or falsity consists in the agreement or disagreement of its sense with reality. | |

| 2.223 | To tell* whether a picture is true or false, we must compare it with reality. |

| 2.224 | It is impossible to tell from the picture alone whether it is true or false. | |

|---|---|---|

| 2.225 | No picture is true a priori. | |

| 3 | A logical picture of facts is a thought. | |

| 3.001 | ’A state-of-things is thinkable’ means: we can picture it.* | |

| 3.01 | The totality of true thoughts is a picture of the world. | |

| 3.02 | A thought contains the possibility of the state of affairs that is thought. What is thinkable is also possible. | |

| 3.03 | We cannot think anything illogical, since otherwise we would have to think illogically. | |

| 3.031 | It was once said that God could create anything except what was contrary to the laws of logic.—In truth, we could not say of an ‘illogical’ world how it would look. | |

| 3.032 | Something that ‘contradicts logic’ cannot be represented in language any more than, in geometry, a figure that contradicts the laws of space can be represented by its coordinates, or the coordinates can be specified of a point that does not exist. | |

| 3.0321 | We can certainly represent a state-of-things spatially that contravenes the laws of physics but not one that contravenes the laws of geometry. | |

| 3.04 | An a priori correct thought would be one whose possibility ensured its truth. | |

| 3.05 | We could only know a priori that a thought is true if its truth could be recognized from the thought itself (without an object of comparison). | |

| 3.1 | In a proposition a thought is expressed perceptibly.* | |

| 3.11 | We use the perceptible sign (sound or written sign, etc.) of the proposition as a projection of a possible state of affairs. The method of projection is the thinking of the proposition’s sense. |

3.12 I call the sign by means of which we express a thought a

propositional sign. And a proposition is a propositional sign in its projective relation to the world.\*

3.13 To the proposition belongs everything that belongs to the projection, but not what is projected.

Thus the possibility of what is projected, but not what is projected itself.

In a proposition its sense is thus not yet contained, but it does contain the possibility of expressing it.\*

(‘The content of a proposition’ means the content of a senseful proposition.\*)

In a proposition the form of its sense is contained, but not its content.

3.14 A propositional sign consists in this, that its elements, the words, stand to one another in it in a determinate way.

A propositional sign is a fact.

3.141 A proposition is not a mixture of words.—(Just as a musical theme is not a mixture of notes.)

A proposition is articulate.

3.142 Only facts can express a sense, a set of names cannot.

3.143 That a propositional sign is a fact is disguised by the ordinary—written or printed—form of expression.

For in a printed proposition, for example, a propositional sign does not look essentially different from a word.

(Thus it was possible for Frege to call a proposition a composite name.)

3.1431 The essence of a propositional sign becomes very clear if we think of it as composed of spatial objects (such as tables, chairs, books) instead of written signs.The relative spatial position of these things then expresses the sense of the proposition.

3.1432 Not: “The complex sign ‘aRb’ says that a stands in the relation R to b”; but: That ‘a’ stands in a certain relation to ‘b’ says that aRb.

3.144 States of affairs can be described, not named. (Names are like points, propositions are like arrows,

they have sense.)

3.2 In a proposition a thought can be so expressed that to the objects of the thought correspond elements of the propositional sign.

3.201 I call these elements ‘simple signs’ and the proposition ‘completely analysed’.

3.202 The simple signs applied in the proposition are called names.

3.203 A name means an object. The object is its meaning.\* (‘A’ is the same sign as ‘A’.)

3.21 The configuration of simple signs in a propositional sign corresponds to the configuration of objects in a state of affairs.

3.22 A name in a proposition stands for an object.

3.221 Objects I can only name. Signs stand for them. I can only speak of them, I cannot state them.\* A proposition can only say how a thing is, not what it is.

3.23 The demand that simple signs be possible is the demand that sense be determinate.\*

3.24 A proposition about a complex stands in an internal relation to a proposition about one of its constituents.

A complex can only be given by its description, and this will be right or not right. A proposition that mentions a complex will not be nonsensical but simply false if the complex does not exist.

That a propositional element signifies a complex can be seen from an indeterminateness in the propositions in which it occurs. We know that not everything is determined by any such proposition. (The generality-sign contains a prototype.\*)

The contraction of a symbol for a complex into a simple symbol can be expressed by a definition.

3.25 There is one and only one complete analysis of a proposition.

3.251 A proposition expresses what it expresses in a determinate, clearly specifiable way: a proposition is articulate.

3.26 A name cannot be dissected further by any definition: it is a primitive sign.

3.261 Every defined sign signifies via those signs by which it is defined; and the definitions point the way.

Two signs, one primitive sign and one defined by primitive signs, cannot signify in the same way. Names cannot be unpacked\* by definitions. (Nor any sign that has a meaning by itself, independently.)

3.262 What does not get expressed in the signs, their application shows. What the signs hold back, their application spells out.\*

3.263 The meanings of primitive signs can be explained by elucidations. Elucidations are propositions that contain the primitive signs. They can therefore only be understood if the meanings of these signs are already known.

3.3 Only a proposition has sense; only in the context of a proposition does a name have meaning.\*

3.31 Every part of a proposition that characterizes its sense I call an expression (a symbol).

(The proposition itself is an expression.)

Expression is everything essential to the sense of a proposition that propositions can have in common with one another.

An expression marks a form and a content.

3.311 An expression presupposes the forms of all propositions in which it can occur. It is the common characteristic mark of a class of propositions.

3.312 It is thus represented by the general form of the propositions that it characterizes.

That is to say, in this form the expression will be constant and everything else variable.

3.313 An expression is thus represented by a variable whose values are the propositions that contain the expression.

(In the limiting case the variable becomes a constant, the expression a proposition.)

I call such a variable a ‘propositional variable’.

3.314 An expression only has meaning in a proposition. Every variable can be construed as a propositional variable.

(Even a variable name.)

3.315 If we change a constituent of a proposition into a variable, then there is a class of propositions that are all the values of the resulting variable proposition. This class still depends in general on what we mean,\* according to our arbitrary conventions, by parts of the original proposition. However, if we change into variables all those signs whose meaning was arbitrarily determined, then there is still such a class. But this is not now dependent on any convention, only on the nature of the proposition. It corresponds to a logical form—a logical prototype.

3.316 What values a propositional variable may take is fixed. The fixing of the values is the variable.\*

3.317 The fixing of the values of propositional variables is the specification of the propositions whose common mark is the variable.

The fixing is a description of these propositions.

The fixing will thus be a matter only of symbols, not of their meaning.

And only this is essential to the fixing, that it is only a description of symbols and states nothing about what is signified.

The way in which the propositions are described is inessential.

3.318 I construe a proposition—like Frege and Russell—as a function of the expressions contained in it.

3.32 A sign is what can be perceived of the symbol.

3.321 Two different symbols can thus have a sign (written or spoken, etc.) in common with one another—they then signify in different ways.

3.322 It can never indicate a common mark of two objects that we signify them by the same sign but through two different modes of signification. For the sign, of course, is arbitrary. Two different signs could just as well be chosen, and what would then remain of something common in the signification?

3.323 In everyday language it occurs extremely often that the same word signifies in different ways—that is, belongs to different symbols—or that two words, which signify in different ways, are applied in a proposition in ostensibly the same way.

Thus the word ‘is’ appears as a copula, as an identity sign, and as an expression of existence;\* ‘exist’ as an intransitive verb like ‘go’; ‘identical’ as an adjective; we talk of something, but also say that something happens.

(In the proposition ‘Green is green’—where the first word is a person’s name, the last an adjective—these words do not simply have different meaning but involve different symbols.)

3.324 Thus the most fundamental confusions easily arise (of which the whole of philosophy is full).

3.325 To avoid these errors, we must use a sign-language that excludes them, by not using the same sign in different symbols, and not using signs that signify in different ways in ostensibly the same way. A sign-language, that is, that obeys logical grammar—logical syntax.

(Frege’s and Russell’s concept-script\* is one such language, though it still fails to exclude all mistakes.)

3.326 To recognize the symbol by its sign, one must pay attention to the senseful use.\*

3.327 A sign determines a logical form only together with its logical-syntactic use.

3.328 If a sign is not needed, then it is meaningless. That is the point of Occam’s razor.\*

(If everything in the sign-language works as though a sign had meaning, then it does have meaning.\*)

3.33 In logical syntax the meaning of a sign should never play a role; it must permit being drawn up without talk of the meaning of a sign; it should presuppose only the description of the expressions.

3.331 This remark gives us insight into Russell’s ‘theory of types’:\* Russell’s error is shown in his having to talk of the meaning of signs in drawing up the rules for them.

3.332 No proposition can state anything about itself, since a propositional sign cannot be contained in itself (that is all there is to the ‘theory of types’).

3.333 That is why a function cannot be its own argument, since the function sign already contains the prototype of its argument and thus cannot contain itself.

For let us suppose that the function F( fx) could be its own argument; there would then be a proposition ‘F(F( fx))’, and in this the outer function F and the inner function F must have different meanings, for the inner has the form ϕ( fx), the outer the form ψ(ϕ( fx)). The two functions only have in common the letter ‘F’, but this by itself signifies nothing.

This becomes immediately clear if, instead of ‘F(F(u)’, we write ’(∃ϕ):F(ϕ u).ϕ u=Fu’.

This resolves Russell’s paradox.

3.334 The rules of logical syntax must be self-explanatory,\* once it is known how every single sign signifies.

3.34 A proposition has essential and accidental features.

Accidental are the features that arise from the particular way that the propositional sign is generated. Essential are those that enable the proposition to express its sense.

3.341 The essential in a proposition is thus what all propositions that can express the same sense have in common.

And so too, in general, the essential in a symbol is what all symbols that can fulfil the same purpose have in common.

3.3411 So one could say: the real name is what all symbols that can signify an object have in common. It would thus progressively turn out that no kind of composition is essential to a name.\*

3.342 In our notations there is indeed something arbitrary, but this is not arbitrary: that when we have determined something arbitrarily, then something else must be the case. (This arises from the essence of notation.)

3.3421 A particular mode of signification may be unimportant, but it is always important that this is a possible mode of signification. And this is how it is generally in philosophy: the particular proves time and again to be unimportant, but the possibility of each particular tells us something about the essence of the world.

3.343 Definitions are rules for translating from one language into another. Every correct sign-language must be translatable into every other according to such rules: this is what they all have in common.

3.344 What signifies in a symbol is what is common to all those symbols by which it can be replaced according to the rules of logical syntax.

3.3441 One can express, for example, what is common to all notations for truth-functions thus: they have in common that they can all be replaced—for example—by the notation that uses ‘~p’ (‘not-p’) and ‘p v q’ (‘p or q’).(This

typifies the way in which a specific possible notation can tell us something general.)

3.3442 The sign for a complex, too, is not resolved arbitrarily in analysis, so that, say, its resolution might be different in every propositional structure.\*

3.4 A proposition determines a place in logical space. The existence of this logical place is guaranteed by the existence of the constituents themselves, by the existence of the senseful proposition.

3.41 The propositional sign and the logical coordinates: that is the logical place.

3.411 A geometrical and a logical place accord in that both are the possibility of an existence.

3.42 Although a proposition may determine only one place in logical space, nevertheless the whole of logical space must already be given by it.

(Otherwise, by means of negation, logical sum, logical product, etc., more and more new elements—in coordination—would be introduced.)

(The logical scaffolding around a picture determines the logical space. A proposition reaches through the whole of logical space.)

3.5 A propositional sign as applied in thinking is a thought. 4 A thought is a senseful proposition.

4.001 The totality of propositions is language.

4.002 Human beings possess the ability to construct languages in which every sense can be expressed, without having any idea of how and what each word means.—Just as one speaks without knowing how the individual sounds are produced.

Everyday language is a part of the human organism and no less complicated than it.

It is humanly impossible to immediately gather from it

the logic of language.

Language disguises thought. And in such a way that the form of the thought that is clothed cannot be inferred from the outer form of the clothing, because the outer form of the clothing is designed for quite other purposes than to allow the form of the body to be recognized.\*

The tacit agreements underlying the understanding of everyday language are enormously complicated.

4.003 Most of the propositions and questions that have been formulated about philosophical matters are not false but nonsensical. So we cannot answer questions of this kind at all, but only expose their nonsensicality. Most of philosophers’ questions and propositions are due to our not understanding the logic of our language.

(They are of the same kind as the question whether the good is more or less identical than the beautiful.)

And it is no wonder that the deepest problems are really not problems.

4.0031 All philosophy is ‘critique of language’. (Albeit not in Mauthner’s sense.\*) Russell’s merit is to have shown that the apparent logical form of a proposition need not be its real one.

4.01 A proposition is a picture of reality.

A proposition is a model of reality as we conceive it.\*

4.011 At first sight a proposition—as printed out on paper, say does not appear to be a picture of the reality it concerns. But neither does musical notation appear at first sight to be a picture of music, nor our phonetic (alphabetic) notation a picture of our spoken language.

And yet these sign-languages\* prove to be pictures, even in the ordinary sense, of what they represent.

4.012 It is obvious we have a sense of a proposition of the form ‘aRb’ as a picture. Here the sign is obviously a likeness of what is signified.

4.013 And if we penetrate to the essence of this pictoriality, then we see that this is not confounded by apparent irregularities (as in the use of ♯ and ♭ in musical notation).

For these irregularities, too, depict what they are intended to express, just in a different way.

4.014 A gramophone record, the musical thought, the musical notation, the sound waves, all stand to one another in that internal relation of depicting that holds between language and world.

Common to all of them is the logical construction.

(Like the two youths, their two horses and their lilies in the fairy tale.\* They are all in a certain sense one.)

4.0141 That there is a general rule by which the musician can read off the symphony from the score, and that there is a rule by which the symphony can be reconstructed from the line on the gramophone record and from this again—by means of the first rule—construct the score, is what constitutes the internal similarity between these apparently very different things. And this rule is the law of projection which projects the symphony into the language of the musical score. It is the rule for translating this language into the language of the gramophone record.\*

4.015 The possibility of all similes, of the whole pictoriality of our language,\* lies in the logic of depiction.

4.016 To understand the essence of a proposition, consider hieroglyphic script, which depicts the facts that it describes.

And alphabetic script came out of it, without losing what is essential in depiction.

4.02 We see this from our ability to understand the sense of a propositional sign without its having been explained to us.

4.021 A proposition is a picture of reality: for I know the state of affairs it represents if I understand the proposition. And I

understand the proposition without its sense having been explained to me.

4.022 A proposition shows its sense.

A proposition shows how things stand if it is true. And it says that they so stand.\*

4.023 Reality must be fixed by a proposition to elicit either yes or no.\*

To do this, it must be completely described by the proposition.

A proposition is a description of a state-of-things.

Like the description of an object by its external properties, so a proposition describes reality by its internal properties.

A proposition constructs a world by means of a logical scaffolding and that is how one can actually see in the proposition all the logical features of reality if it is true.\* One can draw inferences from a false proposition.

4.024 To understand a proposition is to know what is the case if it is true.

(One can thus understand it without knowing whether it is true.)

One understands it if one understands its constituents.

4.025 The translation of one language into another does not proceed by translating every proposition of one into a proposition of another, but only the constituents of the proposition are translated.\*

(And the dictionary translates not only substantives but also verbs, adjectives, and conjunctions, etc.; and it treats them all alike.)

4.026 The meanings of simple signs (words) must be explained to us for us to understand them.

With propositions, however, we communicate.\*

4.027 It is essential to a proposition that it can convey a new sense to us.

4.03 A proposition must convey a new sense with old expressions.

A proposition conveys a state of affairs to us, and hence must connect essentially to the state of affairs.

And the connection is precisely that it is its logical picture.

A proposition only states something insofar as it is a picture.

4.031 In a proposition a state of affairs is put together experimentally, as it were.

Saying that this proposition has such and such a sense is really saying that this proposition represents such and such a state of affairs.

4.0311 One name stands for one thing, another for another thing, and they are combined with one another; in this way the whole—like a tableau vivant—presents a state-of-things.\*

4.0312 The possibility of a proposition rests on the principle of the representation of objects by signs.

My fundamental thought is that the ‘logical constants’ do not represent. That the logic of facts cannot be represented.\*

4.032 A proposition is a picture of a state of affairs only insofar as it is logically articulated.

(The proposition ‘ambulo’ is composite, too, since its stem with a different ending and its ending with a different stem yield different senses.)

4.04 In a proposition there must be exactly as many things distinguishable as in the state of affairs it represents.

The two must have the same logical (mathematical) multiplicity. (Compare Hertz’s Mechanics, on Dynamic Models.)\*

4.041 This mathematical multiplicity, of course, cannot in its turn be depicted. One cannot get outside it in depiction.

4.0411 Trying to express, for example, what we express by ‘(x).fx’

by putting an index before ‘fx’—as in ‘Gen.fx’—wouldn’t work: we would not know what was being generalized. Trying to register it by an index ‘g’—as in ‘f (xg )’ wouldn’t work either: we would not know the scope of the generality-sign.

Trying to do it by introducing a mark in the argumentplaces—as in ‘(G, G).F(G, G)‘—wouldn’t work: we could not determine\* the identity of the variables. And so on.

All these modes of signification do not work because they do not have the necessary mathematical multiplicity.

4.0412 For the same reason the idealist’s explanation of the seeing of spatial relations via ‘spatial spectacles’ doesn’t work, because it cannot explain the multiplicity of these relations.

4.05 Reality is compared with a proposition.

4.06 A proposition can be true or false only by being a picture of reality.

4.061 If one does not bear in mind that a proposition has a sense that is independent of the facts, then one can easily suppose that true and false are relations between sign and what is signified that are on an equal footing.

One could then say, for example, that ‘p’ signifies in the true way what ‘~p’ signifies in the false way, etc.

4.062 Can’t we communicate with false propositions as we have done up to now with true ones? So long as we know that they are meant to be false. No! For a proposition is true if things are as we say they are by using it; and if we mean ~p by ‘p’, and things are as we mean it, then ‘p’ in the new conception is true and not false.

4.0621 However, it is important that the signs ‘p’ and ‘p’ can say the same. For it shows that nothing in reality corresponds to the sign ''.

The occurrence of negation in a proposition is not necessarily a mark of its sense (~~p = p).

The propositions ‘p’ and ‘~p’ have opposite sense, but one and the same reality corresponds to them.

4.063 A picture to explain the concept of truth: black spot on white paper; the form of the spot can be described by stating for each point of the surface whether it is white or black. The fact that a point is black corresponds to a positive fact, that a point is white (not black) to a negative fact. If I signify a point of the surface (a Fregean truthvalue\*), then this corresponds to the supposition that is put up for judgement, etc. etc.

However, to be able to say that a point is black or white, I must first know when a point is called black and when white; to be able to say that ‘p’ is true (or false), I must have determined under what circumstances I call ‘p’ true, and I thereby determine the sense of the proposition.

The point at which the analogy breaks down is now this: we can indicate a point on the paper without even knowing what white and black are; but nothing at all corresponds to a proposition without sense, since it does not signify a thing (truth-value) whose properties are called, say, ‘false’ or ‘true’; the verb of a proposition is not ‘is true’ or ‘is false’—as Frege supposed—but that which is ‘true’ must already contain the verb.

4.064 Every proposition must already have sense; affirmation cannot give it sense, for what is affirmed is precisely its sense. And the same holds for negation, etc.

4.0641 One could say: negation already relates to the logical place that the negated proposition determines.

The negating proposition determines a different logical place than the negated does.

The negating proposition determines a logical place by means of the logical place of the negated proposition in describing the former as lying outside the latter.

That the negated proposition can again be negated alone

shows that what is negated is already a proposition and not just the preliminary to a proposition.

4.1 A proposition represents the obtaining and nonobtaining of states-of-things.

4.11 The totality of true propositions is natural science in total (or the totality of the natural sciences).

4.111 Philosophy is not one of the natural sciences.

(The word ‘philosophy’ must mean something that stands above or below, but not next to, the natural sciences.)

4.112 The purpose of philosophy is the logical clarification of thoughts.

Philosophy is not a set of teachings\* but an activity.

A philosophical work consists essentially of elucidations.

Philosophy results not in ‘philosophical propositions’ but in propositions becoming clear.\*

Philosophy should make clear and delimit sharply thoughts that are otherwise, as it were, cloudy and blurred.

4.1121 Psychology is no more akin to philosophy than is any other natural science.Theory of knowledge is the philosophy of psychology.Does not my study of sign-language correspond to the study of thought processes, which philosophers considered so essential to philosophy of logic? Only they usually got entangled in inessential psychological investigations, and there is an analogous danger as well with my method.

4.1122 Darwinian theory has no more to do with philosophy than has any other hypothesis of natural science.

4.113 Philosophy limits the disputable realm of natural science.

4.114 It should delimit the thinkable and thereby the unthinkable. It should limit the unthinkable from within through the thinkable.\*

4.115 It will indicate\* the unsayable by clearly representing the

sayable.

4.116 Everything that can be thought at all can be thought clearly. Everything that can be stated can be stated clearly.\*

4.12 A proposition can represent the whole of reality, but it cannot represent what it must have in common with reality to be able to represent it—the logical form.

To be able to represent the logical form, we would have to be able to position ourselves with a proposition outside logic, that is, outside the world.

4.121 A proposition cannot represent the logical form; the logical form mirrors itself in the proposition.

What mirrors itself in language, language cannot represent.

What expresses itself in language we cannot express by means of language.

A proposition shows the logical form of reality.

It features it.\*

4.1211 A proposition ‘fa’ thus shows that the object a occurs in its sense, two propositions ‘fa’ and ‘ga’ show that they are both about the same object.If two propositions contradict one another, then their structure shows this; likewise, if one follows from the other. And so on.

4.1212 What can be shown cannot be said.

4.1213 Now we understand, too, our feeling that we are in possession of a correct logical conception once everything is in order in our sign-language.

4.122 We can talk in a certain sense of formal properties of objects and states-of-things, or of properties of the structure of facts, and in the same sense of formal relations and relations of structures.

(Instead of ‘property of a structure’ I also say ‘internal property’; instead of ‘relation of structures’ ‘internal relation’.

I introduce these expressions to show the ground of the

widespread confusion among philosophers between internal relations and real (external) relations.)

The obtaining of such internal properties and relations, however, cannot be asserted by means of propositions, but shows itself in the propositions that represent the relevant states-of-things and concern the relevant objects.

4.1221 An internal property of a fact we can also call a feature of the fact. (In the sense in which we speak, say, of facial features.)

4.123 A property is internal if it is unthinkable that its object does not have it.

(This blue colour and that one stand in the internal relation of lighter and darker eo ipso. It is unthinkable that these two objects should not stand in this relation.)

(Here to the shifting use of the words ‘property’ and ‘relation’ there corresponds the shifting use of the word ‘object’.)

4.124 The obtaining of an internal property of a possible state of affairs is not expressed by a proposition, but expresses itself in the proposition that represents the state of affairs by an internal property of the proposition.

It would be just as nonsensical to ascribe a formal property to a proposition as to deny its ascription.

4.1241 Forms cannot be distinguished from one another by saying that one has this and another has that property, since this presupposes that it makes sense to predicate the two properties to the two forms.

4.125 The obtaining of an internal relation between possible states of affairs expresses itself linguistically by an internal relation between the propositions that represent them.

4.1251 This resolves the dispute ‘whether all relations are internal or external’.

4.1252 Series that are ordered by internal relations I call formseries.

The number series is ordered not by an external but by an internal relation.

Just as in the series of propositions’aRb’,’(∃x):aRx.xRb’,’(∃x,y):aRx.xRy.yRb’,and so forth.(If b stands in one of these relations to a, then I call b a successor of a.)

4.126 In the sense in which we speak of formal properties, we can also talk of formal concepts.

(I introduce this expression to make clear the ground of the confusion of formal concepts with real concepts, which pervades the whole of the old logic.)

That something falls under a formal concept, as one of its objects, cannot be expressed by a proposition. Rather, it shows itself in the sign for the object itself. (A name shows that it signifies an object, a numerical sign that it signifies a number, etc.)

Formal concepts, unlike real concepts,\* cannot be represented by a function.

For its marks, the formal properties, are not expressed by functions.

The expression of a formal property is a feature of certain symbols.

The sign of the marks of a formal concept is thus a characteristic feature of all symbols whose meanings fall under the concept.

The expression of a formal concept is thus a propositional variable, in which only this characteristic feature is constant.

4.127 The propositional variable signifies the formal concept, and its values signify the objects that fall under the concept.

4.1271 Every variable is the sign of a formal concept.For every variable represents a constant form that all its values have, and which can be taken as a formal property of these values.

4.1272 The variable name ‘x’ is thus the real sign of the pseudo-

concept\* object.Wherever the word ‘object’ (‘thing’, ‘entity’, etc.) is correctly used, it is expressed in a conceptscript by a variable name.For example, in the proposition ‘There are 2 objects which…’ by ’(∃x,y)…’.Wherever it is used differently, that is, as a real concept-word, nonsensical pseudo-propositions arise.So one cannot say, for example, ‘There are objects’ as one might say ‘There are books’. Nor is ‘There are 100 objects’ or ‘There are ℵ0 objects’ any better.And it is nonsensical to speak of the number of all objects.The same applies to the words ‘complex’, ‘fact’, ‘function’, ‘number’, etc.They all signify formal concepts and are represented in a concept-script by variables, not by functions or classes (as Frege and Russell held).Expressions such as ‘1 is a number’, ‘there is only one zero’ and the like are nonsensical.(It is just as nonsensical to say ‘There is only one 1’ as it would be to say ‘2 + 2 at 3 o’clock equals 4’.)

4.12721 A formal concept is already given with an object that falls under it. So one cannot introduce as primitive ideas\* the objects of a formal concept and the formal concept itself. So one cannot, for example, introduce as primitive ideas the concept of a function as well as specific functions (as Russell does), or the concept of number and particular numbers.

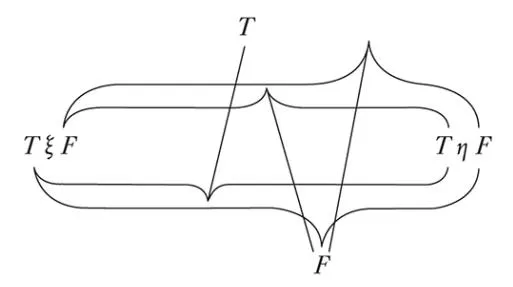

4.1273 If we want to express the general proposition ‘b is a successor of a’ in a concept-script, then we need for this an expression for the general term of the form-series:

, , , …

The general term of a form-series can only be expressed by a variable, since the concept ‘term of this form-series’ is a formal concept. (Frege and Russell overlooked this: the way in which they want to express general propositions such as the above is therefore false; it contains a vicious circle.)

We can determine the general term of a form-series by giving its first term and the general form of the operation that generates the next term from the preceding term.

4.1274 The question as to the existence of a formal concept is nonsensical. For no proposition can answer such a question.

(So, for example, one cannot ask: ‘Are there unanalysable subject–predicate propositions?‘)

4.128 Logical forms are numberless.

That is why there are no pre-eminent numbers\* in logic and why there is no philosophical monism or dualism, etc.

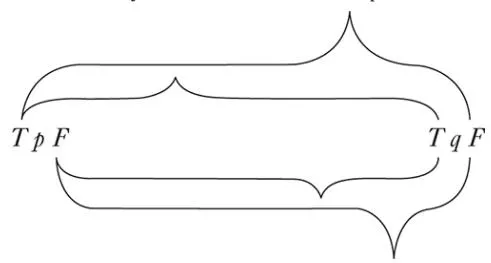

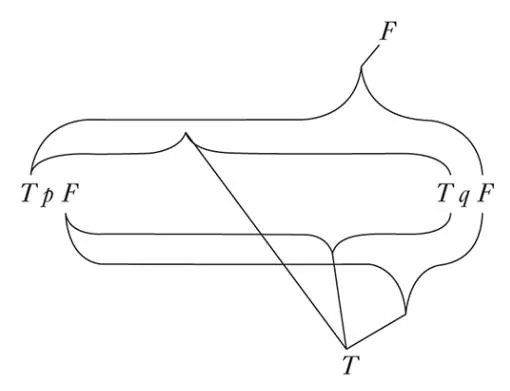

4.2 The sense of a proposition is its agreement and disagreement with the possibilities of the obtaining and non-obtaining of states-of-things.

4.21 The simplest proposition, an elementary proposition, asserts the obtaining of a state-of-things.

4.211 A sign of an elementary proposition is that no elementary proposition can contradict it.

4.22 An elementary proposition consists of names. It is a connection, a concatenation, of names.

4.221 It is obvious that, in the analysis of propositions, we must arrive at elementary propositions, which consist of names in immediate combination.

This raises the question as to how the propositional unity\* comes about.

4.2211 Even if the world is infinitely complex, so that every fact consists of infinitely many states-of-things and every stateof-things is composed of infinitely many objects, there must still be objects and states-of-things.

4.23 A name occurs in a proposition only in the context\* of an elementary proposition.

4.24 Names are the simple symbols; I indicate them by single letters (‘x’, ‘y’, ‘z’).

I write an elementary proposition as a function of names in the form: ‘fx’, ‘ϕ(x, y)’, etc.

Or I indicate it by the letters p, q, r.

4.241 If I use two signs with one and the same meaning, then I express this by placing the sign ’=’ between them.

‘a = b’ thus means:\* the sign ‘a’ is replaceable by the sign ‘b’.

(If I introduce a new sign ‘b’ by an equation, by stipulating that it may replace an already known sign ‘a’, then (like Russell) I write the equation —definition—in the form ‘a = b Def.’. A definition is a rule for signs.)

4.242 Expressions of the form ‘a = b’ are thus only representational aids; they state nothing about the meaning of the signs ‘a’, ‘b’.

4.243 Can we understand two names without knowing whether they signify the same thing or two different things?—Can we understand a proposition in which two names occur without knowing whether they mean the same or different things?

If I know, say, the meaning of an English word and a German word that means the same, then it is impossible for me not to know that they mean the same;\* it is impossible that I cannot translate one into the other.

Expressions such as ‘a = a’, or ones derived from them, are neither elementary propositions nor any other kind of senseful signs. (This will be shown later.)

4.25 If an elementary proposition is true, then the state-of-things obtains; if an elementary proposition is false, then the stateof-things does not obtain.

4.26 The specification of all true elementary propositions describes the world completely. The world is completely described by the specification of all elementary propositions plus the specification as to which of them are true and which false.

4.27 With regard to the obtaining and non-obtaining of n statesof-things there are possibilities.

Any combination of states-of-things can obtain and the others not obtain.

4.28 To these combinations correspond just as many possibilities of the truth—and falsity—of n elementary propositions.

4.3 The truth-possibilities of the elementary propositions mean the possibilities of the obtaining and nonobtaining of states-of-things.

4.31 We can represent the truth-possibilities by schemata of the following kind (‘T’ means ‘true’, ‘F’ ‘false’; the rows of ‘T’ and ‘F’ under the row of the elementary propositions mean their truth-possibilities, in easily understood symbolism):

| p | q | r |

|---|---|---|

| T | T | T |

| F | T | T |

| T | F | T |

| T | T | F |

| F | F | T |

| F | T | F |

| T | F | F |

| F | F | F |

| p | q |

|---|---|

| T | T |

| F | T |

| T | F |

| F | F |

| p | |

|---|---|

| T | |

| F |

4.4 A proposition is the expression of agreement and disagreement with the truth-possibilities of the elementary propositions.

4.41 The truth-possibilities of elementary propositions are the conditions of the truth and falsity of propositions.

4.411 From the outset\* it is likely that the introduction of elementary propositions is fundamental to the understanding of all other kinds of proposition. Indeed, the understanding of general propositions depends palpably on that of elementary propositions.

4.42 With regard to the agreement and disagreement of a proposition with the truth-possibilities of n elementary propositions there are possibilities.

4.43 We can express agreement with the truth-possibilities by correlating, say, the letter ‘T’ (‘true’) with them in the schema.

Absence of this letter means disagreement.

4.431 The expression of the agreement and disagreement with the truth-possibilities of elementary propositions expresses the truth-conditions of a proposition.

A proposition is the expression of its truth-conditions.

(Frege was thus quite right in beginning with these in explaining the signs of his concept-script.\* It is just that Frege’s explanation of the concept of truth is incorrect: If ‘the True’ and ‘the False’ were really objects and the arguments in p etc., then on Frege’s account, the sense of ‘p’ would in no way be determined.)

4.44 The sign that arises from correlating the letter ‘T’ with the truth-possibilities is a propositional sign.

4.441 It is clear that no object (or complex of objects) corresponds to the complex of the signs ‘F’ and ‘T’, any more than to the horizontal and vertical lines or to brackets. —There are no ‘logical objects’.

This holds similarly, of course, for all signs that express the same as the schemata of ‘T’ and ‘F’.

4.442 This, for example, is a propositional sign:

| p | q | |

|---|---|---|

| T | T | T |

| F | T | T |

| T | F | |

| F | F | T |

(Frege’s ‘judgement stroke’ ’⊢’ is logically quite meaningless; it only indicates for Frege (and Russell) that they hold the propositions so signified to be true.\* ’⊢’ thus forms no part of propositional structure any more than does, say, a proposition’s number. It is impossible for a proposition to state of itself that it is true.)

If the sequence of truth-possibilities in a schema is fixed once and for all by a rule of combination, then the last column by itself is an expression of the truth-conditions. If we write this column down as a row, then the propositional sign becomes: ‘(TTT)(_p,q)’ or better ‘(TTFT)(p,q)’.

(The number of places in the left-hand brackets is determined by the number of terms in the right-hand.)

4.45 For n elementary propositions there are Ln possible groups of truth-conditions.

The groups of truth-conditions that pertain to the truthpossibilities of a number of elementary propositions can be ordered in a series.

4.46 Among the possible groups of truth-conditions there are two extreme cases.

In one case the proposition is true for all the truthpossibilities of the elementary propositions. We say that the truth-conditions are tautologous.

In the second case the proposition is false for all the truth-possibilities: the truth-conditions are contradictory.

In the first case we call the proposition a tautology, in the second a contradiction.

4.461 A proposition shows what it says, a tautology and a contradiction show that they say nothing.

A tautology has no truth-conditions, since it is true unconditionally; and a contradiction is true on no condition.

Tautology and contradiction are senseless.

(Like a point from which two arrows diverge in opposite directions.)

(I know nothing about the weather, for example, when I know that it is raining or not raining.)

4.4611 Tautology and contradiction, however, are not nonsensical; they are part of the symbolism, just like ‘0’ is part of the symbolism of arithmetic.

4.462 Tautology and contradiction are not pictures of reality. They do not represent any possible state of affairs. For the former allows every possible state of affairs, the latter none.

In a tautology the conditions of agreement with the world—the representational relations—cancel one another out, so that it stands in no representational relation to reality.

4.463 The truth-conditions determine the room that a proposition leaves to the facts.

(A proposition, a picture, a model are, in a negative sense, like a solid body that restricts the freedom of movement of another; in a positive sense, like the space limited by solid substance in which a body finds a place.)

A tautology leaves open to reality the whole of—infinite

—logical space; a contradiction fills the whole of logical space and leaves no point open to reality. Neither of them can therefore determine reality in any way.

4.464 The truth of tautology is certain, of propositions possible, of contradiction impossible.\*

(Certain, possible, impossible: here we have an indication of the gradation that we need in probability theory.)

4.465 The logical product of a tautology and a proposition says the same as the proposition. This product is thus identical to the proposition. For the essence of a symbol cannot be altered without altering its sense.

4.466 To a determinate logical combination of signs corresponds a determinate logical combination of their meanings; every arbitrary combination only corresponds to uncombined signs.

That is, propositions that are true for every state of affairs cannot be combinations of signs at all, since, if they were, only determinate combinations of objects could correspond to them.

(And where there is no logical combination there is no corresponding combination of objects.)

Tautology and contradiction are the limiting cases of the combination of symbols,\* namely, their dissolution.

4.4661 Admittedly, signs are combined with one another in tautology and contradiction as well, i.e. they stand in relations to one another, but these relations are meaningless, inessential to the symbol.

4.5 It now appears possible to specify the most general propositional form: that is, to give a description of the propositions of any sign-language, so that every possible sense can be expressed by a symbol that fits the description, and that every symbol that fits the description can express a sense, if the meanings of the names are chosen accordingly.

It is clear that in the description of the most general propositional form only what is essential to it may be described—since otherwise it would not be the most general.

That there is a general propositional form is demonstrated by this: that there cannot be a proposition whose form could not have been foreseen (i.e. constructed). The general form of a proposition is: such and such is the case.\*

4.51 Suppose that I am given all elementary propositions; then the question arises as to what propositions I can form from them. And the answer is all propositions and this is how they are limited.

4.52 Propositions are everything that follows from the totality of all elementary propositions (and also, of course, from its being the totality of all). (So, in a certain sense, one could say that all propositions are generalizations of elementary propositions.)

4.53 The general propositional form is a variable.

5 A proposition is a truth-function of elementary propositions.

(An elementary proposition is a truth-function of itself.)

5.01 Elementary propositions are the truth-arguments of propositions.

5.02 It is easy to confuse the arguments of functions with the indices of names. For I recognize from both an argument and an index the meaning of the sign that contains them.

In Russell’s ‘+c ’, for example, ‘c’ is an index that indicates that the whole sign is the addition sign for cardinal numbers. But this designation rests on arbitrary convention and instead of ‘+c ’ a simple sign could be chosen; in ‘p’, however, ‘p’ is not an index but an argument: the sense of ‘p’ cannot be understood without

prior understanding of the sense of ‘p’. (In the name ‘Julius Caesar’ ‘Julius’ is an index. The index is always part of a description of the object to whose name we attach it. For example, the Caesar of the gens Julia.)

The confusion of argument and index underlies, if I am not mistaken, Frege’s theory of the meaning of propositions and functions. For Frege the propositions of logic were names and their arguments the indices of these names.

5.1 The truth-functions can be ordered in series. This is the foundation of probability theory.

5.101 The truth-functions of any number of elementary propositions can be written down in a schema of the following kind:\*

(TTTT) (p,q) Tautology (If p, then p; and if q, then q.)[p⊃p. q⊃q](FTTT) (p,q) in words: Not both p and q. [~(p.q)](TFTT) (p,q) " " If q, then p. [q⊃p](TTFT) (p,q) " " If p, then q. [p⊃q](TTTF) (p,q) " " p or q. [pvq](FFTT) (p,q) " " Not q.[~ q](FTFT) (p,q) " " Not p. [~p](FTTF) (p,q) " " p or q, but not both. [p.~q: v : q.~p](TFFT) (p,q) " " If p, then q; and if q, then p. [p≡q](TFTF) (p,q) " " p(TTFF) (p,q) " " q(FFFT) (p,q) " " Neither p nor q. [~p.~q or p|q](FFTF) (p,q) " " p and not q. [p.~q](FTFF) (p,q) " " q and not p. [q.~p](TFFF) (p,q) " " p and q. [p.q](FFFF) (p,q) Contradiction (p and not p; and q and not q.)[p.~p. q.~q]Those truth-possibilities of its truth-arguments that make a proposition true I will call its truth-grounds.

5.11 If the truth-grounds that are common to a number of propositions are all also truth-grounds of a particular proposition, then we say that the truth of this proposition follows from the truth of those propositions.

5.12 In particular, the truth of a proposition ‘p’ follows from the truth of another proposition ‘q’ if all truth-grounds of the second are truth-grounds of the first.

5.121 The truth-grounds of the one are contained in those of the other; p follows from q.

5.122 If p follows from q, then the sense of ‘p’ is contained in the sense of ‘q’.

5.123 If a god creates a world in which certain propositions are true, then he thereby creates a world in which all their consequences are true as well. And similarly he could not create a world in which a proposition ‘p’ is true without creating all its objects.

5.124 A proposition affirms every proposition that follows from it.

5.1241 ‘p.q’ is one of the propositions that affirm ‘p’ and at the same time one of the propositions that affirm ‘q’.Two propositions are opposed to one another if there is no senseful proposition that affirms them both.Every proposition that contradicts another negates it.

5.13 That the truth of one proposition follows from the truth of other propositions can be seen from the structure of the propositions.

5.131 If the truth of one proposition follows from the truth of others, then this expresses itself through relations in which the forms of these propositions stand to one another; that is to say, we do not need to first put them in these relations by combining them with one another in one proposition;

rather, these relations are internal and obtain as soon as, and in virtue of, these propositions obtaining.

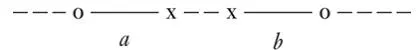

5.1311 If we infer q from p v q and p, then the relation between the propositional forms of ‘p v q’ and ‘p’ is here concealed by the mode of signification. But if we write, for example, ‘p|q.|.p|q’ instead of ‘p v q’ and ‘p|p’ instead of ‘~p’ (p|q =neither p nor q), then the inner connection becomes manifest.(That fa can be inferred from (x).fx shows that the generality is present also in the symbol ‘(x).fx’.)

5.132 If p follows from q, then I can take q to infer p, deduce p from q.

The kind of inference is to be gathered from the two propositions alone.

Only they themselves can justify the inference.

‘Laws of inference’, which are supposed—e.g. by Frege and Russell—to justify inferences, are senseless, and would be superfluous.

5.133 All deduction proceeds a priori.

5.134 From an elementary proposition no other can be deduced.

5.135 In no way can an inference be drawn from the obtaining of any one state of affairs to the obtaining of another, completely different state of affairs.

5.136 There is no causal nexus that would justify such an inference.

5.1361 We cannot infer future events from present ones.Superstition is the belief in the causal nexus.\*

5.1362 Freedom of the will consists in not yet being able to know future actions. We could only know them if causality were an inner necessity, like that of logical inference.—The connection between knowledge and what is known is that of logical necessity.(‘A knows that p is the case’ is senseless if p is a tautology.)

5.1363 If it does not follow from a proposition’s being self-evident

that it is true, then its self-evidence is no justification, either, for our belief in its truth.\*

5.14 If a proposition follows from another, then the latter says more than the former, the former less than the latter.

5.141 If p follows from q and q from p, then they are one and the same proposition.

5.142 A tautology follows from all propositions: it says nothing.

5.143 Contradiction is what is common to propositions that no proposition has in common with another. Tautology is what is common to all propositions which have nothing in common with one another.

Contradiction vanishes, so to speak, outside, tautology inside all propositions.

Contradiction is the outer limit of propositions, tautology the empty point at their centre.\*

5.15 If Tr is the number of the truth-grounds of a proposition ‘r’, Trs the number of the truth-grounds of a proposition ‘s’ that are also truth-grounds of ‘r’, then we call the ratio Trs:Tr the measure of probability that the proposition ‘r’ gives to the proposition ‘s’.

5.151 In a schema like that above in 5.101, let Tr be the number of the ‘T’s in the proposition r, Trs the number of the ‘T’s in the proposition s that are in the same columns as ‘T’s of the proposition r. The proposition r then gives to the proposition s the probability: Trs:Tr .

5.1511 There is no special object that is peculiar to probability propositions.

5.152 Propositions that have no truth-arguments in common with one another we call independent of one another.

Two elementary propositions give one another the probability ½.

If p follows from q, then the proposition ‘q’ gives to the proposition ‘p’ the probability 1. The certainty of logical

inference is a limiting case of probability.

(Application to tautology and contradiction.)

5.153 A proposition is in itself neither probable nor improbable. An event occurs or it does not occur; there is no middle case.

5.154 Suppose that in an urn there are just as many white as black balls (and no others). I draw one ball after another and put them back again in the urn. I can then establish by experiment that the numbers of drawn black and white balls converge as the draw continues.

This is therefore not a mathematical factum.\*

If I now say, ‘It is equally probable that I will draw a white as a black ball’, then this is to say, ‘All the circumstances known to me (including the laws of nature hypothetically assumed) give to the occurrence of the one event no more probability than to the occurrence of the other’. That is, they give to each—as is easily gathered from the explanations above—the probability ½.

What I confirm by the experiment is that the occurrence of the two events is independent of the circumstances of which I know nothing further.

5.155 The unit of a probability proposition is this: the circumstances—of which I know nothing more—give to the occurrence of a definite event such and such a degree of probability.

5.156 Probability is thus a generalization.

It involves a general description of a propositional form.

Only when certainty is lacking do we use probability.— That is, when we do not fully know a fact, but do know something about its form.

(A proposition can indeed be an incomplete picture of a certain state of affairs, but it is always a complete picture.)

A probability proposition is, as it were, an extract\* from other propositions.

relations to one another.

5.21 We can bring out these internal relations in our mode of expression, by representing a proposition as the result of an operation that generates it from other propositions (the bases of the operation).

5.22 An operation is the expression of a relation between the structures of its result and its bases.

5.23 An operation is what must happen to a proposition to make another out of it.

5.231 And that will depend, of course, on their formal properties, on the internal similarity of their forms.

5.232 The internal relation that orders a series is equivalent to the operation that generates one term from another.

5.233 An operation can only arise where a proposition is generated from another in a logically significant way; that is, where the logical construction of the proposition begins.

5.234 Truth-functions of elementary propositions are results of operations that have the elementary propositions as bases. (I call these operations truth-operations.)

5.2341 The sense of a truth-function of p is a function of the sense of p.Negation, logical addition, logical multiplication, etc., etc., are operations.(Negation reverses the sense of a proposition.)

5.24 An operation shows itself in a variable; it shows how one can get from one form of proposition to another.

It gives expression to the difference between the forms. (And what is common to the bases and the result of the operation is precisely the bases.)

5.241 An operation does not mark a form but only the difference between forms.

5.242 The same operation that generates ‘q’ from ‘p’ also generates ‘r’ from ‘q’, and so forth. This can only be

expressed by ‘p’, ‘q’, ‘r’, etc. being variables that give expression in a general way to certain formal relations.

5.25 The occurrence of an operation does not characterize the sense of a proposition.

For nothing is stated by the operation, only by its result, and this depends on the bases of the operation.

(Operation and function must not be confused with one another.)

5.251 A function cannot be its own argument, but the result of an operation can certainly become its own base.

5.252 Only in this way is the progression possible from term to term in a form-series (from type to type in Russell and Whitehead’s hierarchies). (Russell and Whitehead did not admit the possibility of this progression, but made use of it again and again.)

5.2521 The repeated application of an operation to its own result I call its successive application (‘O’O’O’a’ is the result of three successive applications of ‘O’ξ’ to ‘a’).In a similar sense I talk of the successive application of several operations to a number of propositions.

5.2522 The general term of a form-series a, O’a, O’O’a,…I thus write as follows: ‘[a, x, O’x]’. This bracketed expression is a variable. The first term of the bracketed expression is the beginning of the form-series, the second the form of an arbitrary term x of the series, and the third the form of the term of the series that immediately follows x.

5.2523 The concept of the successive application of an operation is equivalent to the concept ‘and so on’.

5.253 An operation can reverse the effect of another. Operations can cancel one another.

5.254 An operation can vanish (for example, negation in ‘~~p’; ~~p = p).

5.3 All propositions are results of truth-operations on elementary propositions.

A truth-operation is the way in which a truthfunction arises from elementary propositions.

It is of the essence of a truth-operation that, in the same way as elementary propositions give rise to their truth-function, truth-functions give rise to a new one. Every truth-operation generates, from truth-functions of elementary propositions, another truth-function of elementary propositions, a proposition. The result of every truth-operation on the results of truth-operations on elementary propositions is also the result of one truth-operation on elementary propositions.

Every proposition is the result of truth-operations on elementary propositions.

5.31 The schemata in 4.31 also have a meaning, then, when ‘p’, ‘q’, ‘r’, etc. are not elementary propositions.

And it is easy to see that the propositional sign in 4.442 expresses one truth-function of elementary propositions even when ‘p’ and ‘q’ are truth-functions of elementary propositions.

5.32 All truth-functions are results of the successive application of a finite number of truth-operations to elementary propositions.

5.4 This shows that there are no ‘logical objects’, no ‘logical constants’ (in Frege’s and Russell’s sense).

5.41 For all results of truth-operations on truth-functions are identical whenever they are one and the same truthfunction of elementary propositions.

5.42 That v, ⊃, etc. are not relations in the sense of right and left, etc., is evident.

The interdefinability of Frege’s and Russell’s ‘primitive signs’ of logic shows in itself that these are not primitive signs and, even more, that they do not signify relations.

And it is obvious that the ’⊃’ that we define by means of ’~’ and ‘v’ is identical with the one by means of which,

with ’~’, we define ‘v’, and that this ‘v’ is identical with the first; and so on.

5.43 It is surely hard to believe\* that from one fact p infinitely many others should follow, namely, ~~p, ~~~~p, etc. And no less remarkable is it that the infinite number of propositions of logic (mathematics) follow from half a dozen ‘primitive propositions’.\*

All propositions of logic, however, say the same. Namely, nothing.

5.44 Truth-functions are not material functions.

If an affirmation, for example, can be generated by double negation, then is negation—in some sense contained in affirmation? Does ‘~~p’ negate ~p, or does it affirm p, or both?

The proposition ‘~~p’ is not concerned with negation as if it were an object; but the possibility of negation is certainly already presupposed in affirmation.

And if there were an object called ’~’, then what ‘~~p’ and ‘p’ say would have to be different. For the one proposition would then be concerned with ~, the other not.

5.441 This vanishing of the apparent logical constants also occurs where ’(∃x).fx’ says the same as ‘(x).fx’, or ’(∃x). fx.x = a’ the same as ‘fa’.

5.442 If a proposition is given to us, then with it are also given the results of all truth-operations that have it as their base.

5.45 If there are primitive signs of logic, then a correct logic must make clear their relation to one another and justify their occurrence.\* The construction of logic out of its primitive signs must become clear.

5.451 If logic has primitive ideas, then they must be independent of one another. If a primitive idea is introduced, then it must be introduced in all combinations in which it occurs whatsoever. It cannot be introduced, that is, first for one combination and then once more for another. For example,

if negation is introduced, then it must now be the case that we understand it in propositions of the form ‘p’ as well as in propositions such as ‘(pvq)’, ’(∃x).~fx’, among others. We must not introduce it first for one class of cases, then for another, for it would then be left in doubt whether its meaning is the same in the two cases and there would be no reason given for using the same kind of sign-combination in the two cases.

(In short, what Frege said (in Basic Laws of Arithmetic) about the introduction of signs by means of definitions also holds, mutatis mutandis, for the introduction of primitive signs.\*)

5.452 The introduction of a new aid into the symbolism of logic must always be an event of consequence. No new aid may be introduced in logic—with a quite innocent face, so to speak—in brackets or in the margins.

(This is how definitions and primitive propositions appear in words in Russell and Whitehead’s Principia Mathematica.\* Why suddenly words here? Justification is needed. This is missing and is bound to be missing, since the practice is in fact illegitimate.)

If the introduction of a new aid has proved necessary at a certain point, however, then the question must immediately be asked: Where must this aid now always be applied? Its place in logic must now be explained.

5.453 All numbers in logic have to be justified.

Or rather: it must turn out that there are no numbers in logic.

There are no pre-eminent numbers.\*

5.454 In logic there is no juxtaposition,\* there can be no classification.

In logic there cannot be degrees of generality and specificity.

5.4541 The solutions of the problems of logic must be simple, for they set the standard of simplicity.People have always

suspected that there must be a realm of questions whose answers—a priori—lie symmetrically united in a selfcontained, regular structure.A realm in which the proposition holds: simplex sigillum veri.\*

5.46 If the logical signs were introduced correctly, then the sense of all their combinations would thereby also have been introduced; that is, not only ‘pvq’ but also ‘(pvq)’, etc. etc. The effect of all possible combinations of brackets would thereby also have been introduced. And it would then have become clear that the real general primitive signs are not ‘pvq’, ’(∃x).fx’, etc., but the most general form of their combinations.

5.461 Of great significance is the apparently unimportant fact that pseudo-relations in logic, such as v und ⊃, need brackets, unlike real relations.

For the use of brackets with these apparently primitive signs already indicates that they are not the real primitive signs. And no one could possibly believe that brackets have an independent meaning.

5.4611 Signs for logical operations are punctuation marks.

5.47 It is clear that everything that can be said from the outset about the form of all propositions must be capable of being said all at once.

For all logical operations are already contained in the elementary proposition. For ‘fa’ says the same as ’(∃x).fx.x = a’.

Where there is compositionality, there is argument and function, and where these are, there are already all logical constants.

One could say: the one logical constant is what all propositions, by their nature, have in common with one another.

But that is the general propositional form.

5.471 The general propositional form is the essence of the proposition.

5.4711 To specify the essence of the proposition is to specify the essence of all description, and thus the essence of the world.

5.472 The description of the most general propositional form is the description of the one and only general primitive sign in logic.

5.473 Logic must take care of itself.